The Green Man made it to Canada at the end of the 19th century, carved into the Parliamentary Library. Then the 20th century brought new life to this leafy medieval face: he moved from sacred sites, inns and pubs, into literature and film.

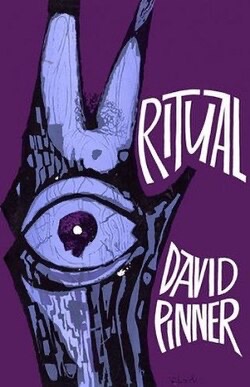

It is surely the modern mind that makes a tree spirit or a spirit of vegetation into a horror movie. The 1973 film, “The Wicker Man,” is based on the 1967 novel Ritual by David Pinner; not surprisingly, the investigating policeman stays in the Green Man Inn… This is one helluva scary movie. Or should I say “folk horror,” which is how IMDb classifies a 21st century film about a pagan ritual, the 2019 “Midsommar.”

Kingsley Amis also offered up a modern take on The Green Man in his 1969 novel of the same name. In addition to Amis’s usual mix of a male narrator who drinks too much while on the misogynistic make, this novel takes on a pedophilic ghost, a definition of ghosts, a conversation with god about life after death, immortality, and finally, the Green Man in the form of a murderous monster restored to life to do the bidding of aforesaid ghost. The story takes place in and around a pub/inn called The Green Man.

Amis’s narrator Maurice Allingham considers the name of his inn: “The Green Man. Dozens, perhaps hundreds, of English pubs and inns bear the name, in reference, I remembered reading somewhere, either to a Jack-in-the-green, a character in traditional May Day revels, or merely to a gamekeeper, who would formerly have worn some kind of green suit.” (p. 108) As the narrator looks into the past of his inn, it becomes clear that Amis is satirising our nostalgia for the past: watch out what you wish for, because you might find out that the house’s ghost was a pedophile who resuscitated a leafy-branched monster.

The Green Man that later attacks Allingham is no “merely.” “A tall and immensely broad figure came stumping awkwardly along the track, massive legs, apparently of not quite the same length, pounding away with the implacable vigour of machinery, long arms pumping in an imperfectly synchronized rhythm. … it was made up of lumps of timber, some with thickly ribbed bark, some with a thin glistening skin, of bundles of twigs and of ropes and compressed masses of green and dead and rotting leaves.” (p. 105) “I saw its face now for the first time, an almost flat surface of smooth dusty bark like the trunk of a Scotch pine, with irregular eye-sockets in which a fungoid luminescence glimmered, and a wide grinning mouth that showed more than a dozen teeth made of jagged stumps of rotting wood … foliage issuing from its mouth…” (p. 157)

What does our modern revulsion towards the spirit of vegetation say about our relationship with nature today? The Beltane Fire Society website has a live Green Man who has startling ideas on his role in the context of nature today.

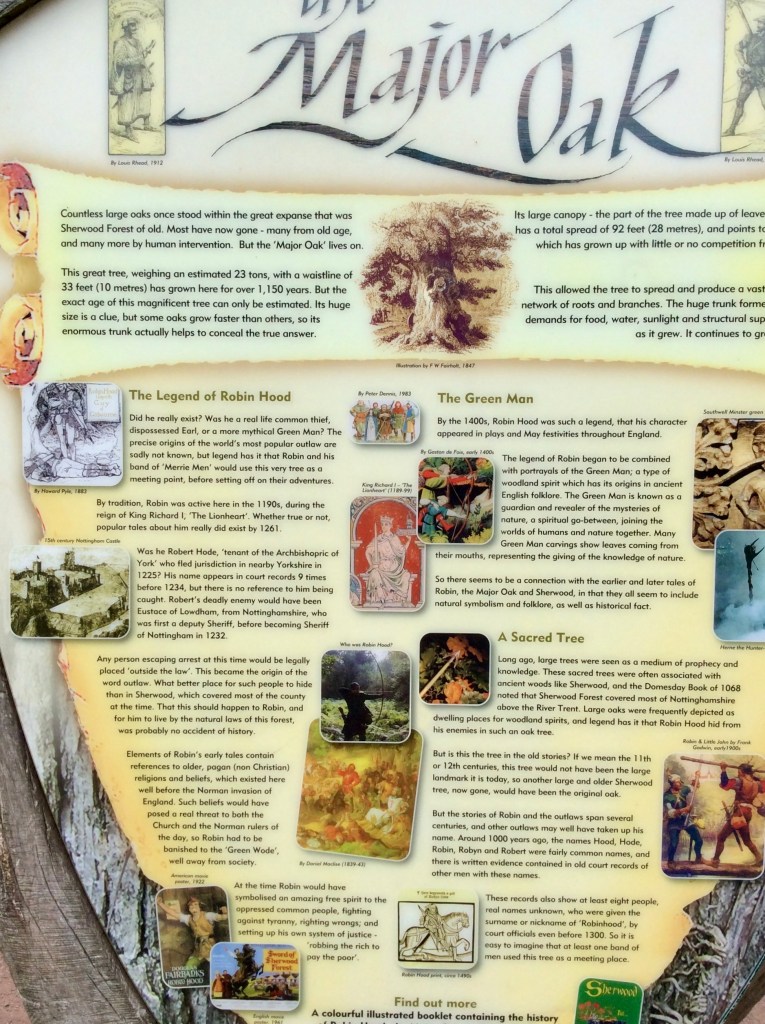

On the other hand, in England, an old oak is treasured, and linked to both Robin Hood and the Green Man:

Some Green Man books listed on the website of Library and Archives Canada:

- The Green Man by Michael Bedard, Tundra Books, 2012

- Green Man: Poems by John Donland, Ronsdale Press, 1999

- The Green Man by Frances Roberts, Beret Days Press, 2005

- The Green Man by Henry Treece, 1968

Donlan’s Green Man cover is of a corbel in the church of Saint Jerome in Llangwm, Monmouthshire, reproduced in The Green Man: The Archetype of Our Oneness With the Earth by William Anderson, HarperCollins, 1990.

I cited this edition of Amis’s novel: The Green Man (first published by Jonathan Cape 1969); rpt. Panther Books paperback 1971.